All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

New Perspective of Multi-dimensional Approach for the Management of Attention-deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Review

Abstract

One of the most common mental diseases in childhood, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) often lasts into adulthood for many individuals. The neurodevelopmental condition known as ADHD impacts three areas of the brain: hyperactivity, impulsivity, and attention. The visual field is where attention is most affected by ADHD. Non-strabismic binocular vision disorder (NSBVD), which impairs eye coordination and makes it challenging to focus, has been linked to ADHD. Through a critical cognitive process called visual attention, humans are able to take in and organize information from their visual environment. This greatly affects how one observes, processes, and understands visual information in day-to-day living. Vision therapy is a non-invasive therapeutic approach that aims to improve visual talents and address visual attention deficits. This study aims to provide an overview of the research on the many approaches to treating ADHD, the relationship between NSBVD and ADHD, and whether vision therapy is a viable treatment option for ADHD. After a comprehensive search of many online resources, relevant studies were found. The review's findings provide insight into the range of ADHD patients' treatment choices. In order to improve treatment outcomes, non-pharmacological treatments can be employed either alone or in conjunction with medicine. Medicine by itself is insufficient and has several severe side effects when used continuously. The efficacy of vision therapy in improving visual attention and making recommendations for potential directions for further research in this field. Multiple studies are needed to identify the most effective treatment modalities for achieving positive outcomes for ADHD patients.

1. INTRODUCTION

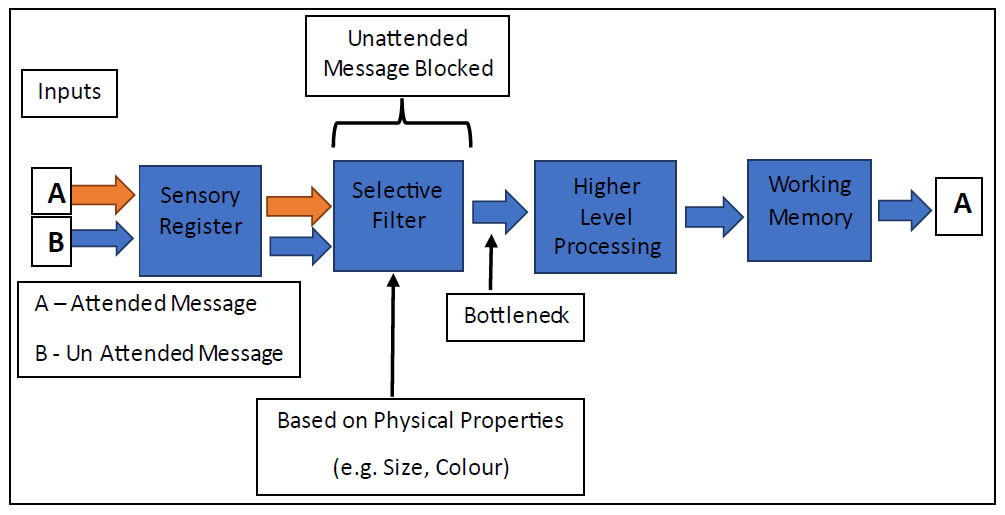

Attention involves the cognitive mechanism of deliberately focusing on particular elements within the environment while disregarding others. It allows individuals to allocate their limited cognitive resources to relevant information, facilitating perception, memory, decision-making, and action [1]. Visual attention is a cognitive process through which humans selectively focus on specific visual stimuli while filtering out irrelevant information. It plays a crucial role in perception, guiding gaze, and allocating cognitive resources to relevant visual elements in our environment [2, 3]. This phenomenon is closely tied to the mechanisms of visual perception, visual search, and object recognition [4, 5]. Understanding visual attention has broad implications for various fields, including psychology, neuroscience, computer vision, and artificial intelligence. Selective attention, divided attention, and sustained attention are some of the different components and processes that make up visual attention. The ability to focus on specific stimuli while filtering out competing distractions was known as selective attention. On the other hand, divided attention entails efficiently allocating attention among numerous inputs or tasks at once [6, 7]. This filtration process was a part of visual information processing where all information reaches a different cognitive level, and whichever place our mind wants to see, that information reaches the highest level of thinking, and people would give attention to that object [8].

1.1. Visual Information Processing

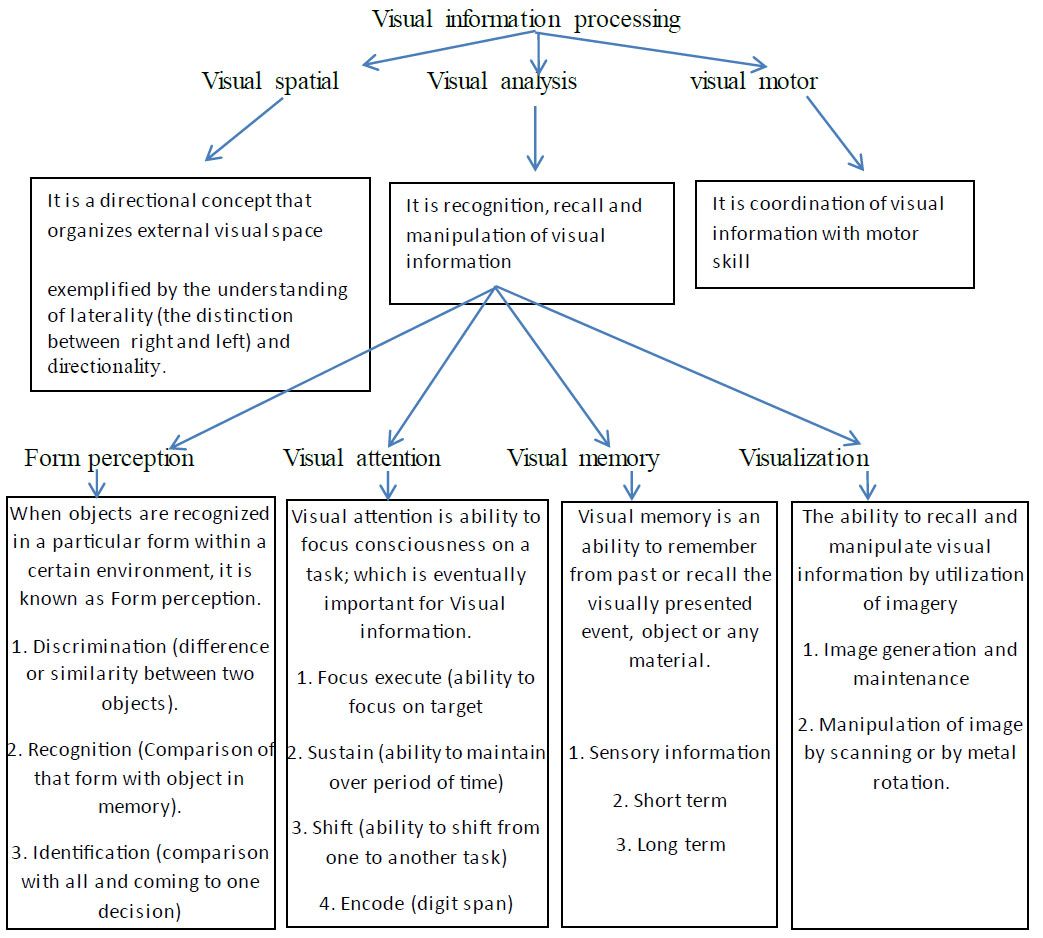

The human visual system is bombarded with an overwhelming amount of visual information processing at any given moment. However, our cognitive resources are limited, and it is not feasible to process all incoming visual stimuli simultaneously. Therefore, visual attention acts as a mechanism that prioritizes relevant information while suppressing or ignoring irrelevant or distracting elements, as shown in Fig. (1). The visual information process was broadly divided into three subsections: visual-spatial, visual analysis, and visual-motor. Visual analysis was further divided into four subsections, as mentioned in Fig. (2) [10-13].

1.2. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

Attention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity are all impacted by the neurodevelopmental conditions called ADHD and ADD. Historically, ADD was used to describe the subtype of ADHD. However, in the current diagnostic criteria, According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), which was shown in Tables 1-2 [14, 15], ADHD is now the umbrella term used to describe both the hyperactive/ impulsive and inattentive subtypes and ADD is no longer used as a separate diagnosis. Both children and adults can be affected by ADHD, which has a substantial negative influence on a number of facets of a person's life, including social relationships, work productivity, and academic achievement [16-18]. ADHD is thought to result from a confluence of genetic, environmental, and neurological factors, however, its specific causes were yet unknown, but a few conditions were directly related to ADHD, like neurotransmitter imbalance, maternal smoking and substance abuse, premature birth, low birth weight, and socioeconomic conditions [19]. Understanding ADHD and its complexities was crucial for effective diagnosis, treatment, and support for those affected by this disorder.

This figure was adapted from Broadbent's Filter Model for Attention (1958) [9] and shows how the multiple unwanted impulses get filtered out and allow only the required information to the brain. In the Figure ‘A’ and ‘B’ are input, and with the help of the sensory pathway, reach selective filtration level where brain understands the information related to objects shape, size, colour and many more and then select only one information that was high-level processing and allow only ‘A’ information, and the memory also recognized the information ‘A’ [9-11]. The prevalence of ADHD varies across different populations and is influenced by various factors, including diagnostic criteria, assessment methods, cultural differences, and sample characteristics [15, 20, 21]. The reported prevalence rates also differ between children and adults. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5), which was widely used for diagnosing ADHD, the prevalence of ADHD in children was approximately 5-10% and 2-5% [15] in adults worldwide. However, prevalence rates can differ among countries. In India, the prevalence rate was 1.30% to 28.9% [20] in children and adolescents, and in north Indian schoolchildren, ADHD prevalence is 6.34% [21]. The attention span decreased after COVID-19 by 54.4% in students, which caused difficulty in academic performance [22]. With appropriate support and interventions, individuals with ADHD can develop strategies to cope with their symptoms, improve their focus and attention, and lead fulfilling lives. During comprehensive eye testing of ADHD symptomatic patients, it was observed that they had some form of binocular vision abnormality like convergence insufficiency 30%, accommodative dysfunction 24%, accommodative with vergence dysfunction 13%, and fusional vergence dysfunction 3%. Seventy-one % of the students reported positive ADHD symptoms, and the majority of the students exhibited inattention issues rather than hyperactivity [23]. Fifty-two% of the kids had non-strabismic binocular vision disorder (NSBVD) and ADHD symptoms. Home-based visual treatment alleviated the attention deficit disorder [24, 25]. NSBVD abnormality refers to an eye condition characterized by an impairment in the coordination and alignment of the two eyes. People with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) have been reported to have NSBVD [23]. In individuals with non-strabismic binocular vision abnormality, the eyes struggle to work together efficiently, leading to difficulties in focusing, tracking moving objects, eye strain, double vision, reduced attention and reading comprehension, and perceiving depth and spatial relationships. Research has shown a higher prevalence of binocular vision abnormalities, such as convergence insufficiency, divergence excess, and accommodative dysfunction, among individuals with ADHD [23, 24, 26]. The exact relationship between ADHD and non-strabismic binocular vision abnormalities is still being explored. It is believed that certain neurological and developmental factors like depression, anxiety, and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) associated with ADHD may contribute to the development or exacerbation of these visual abnormalities [27, 28]. Early detection and diagnosis of non-strabismic binocular vision abnormalities in individuals with ADHD are crucial for appropriate intervention [29]. Visual attention can be improved with the help of vision therapy. Vision therapy is a type of rehabilitation program that involves exercises and activities aimed at improving visual skills and abilities. These skills include eye movement control, focusing abilities, binocular vision, visual processing skills, and attention. The goal of vision therapy is to improve overall visual function, reduce symptoms related to visual dysfunction, and enhance the individual's quality of life [26]. A new technology, which was based on electroencephalography (EEG), was a non-invasive technique to diagnose, measure, and help in vision therapy. The electrical activity of the brain is electroencephalography (EEG), which is aided by a brain-computer interface (BCI). It assists in the diagnosis and management of ADHD patients [30-32].

This figure was adapted from the visual perception book. This Figure shows how visual information processing was divided into visual-spatial, visual analysis, and visual motor for recognition of any objects, and it also shows that visual analyzing was done based on perceptual attention memory visualization.

2. METHODOLOGY

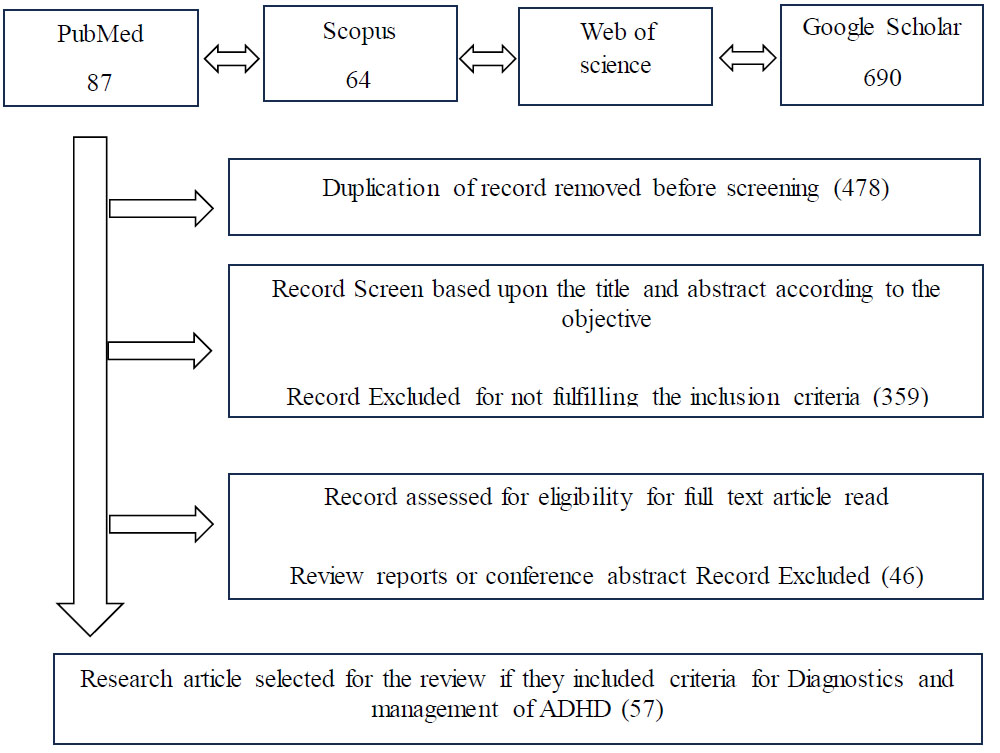

All the articles selected were related to these keywords: “attention deficit disorder” OR “ADD” OR “attention deficit hyperactive symptoms” OR “ADHS” OR “attention deficit hyperactive disorder” OR “ADHD” AND “binocular vision abnormality” OR “non-strabismic binocular vision dysfunction” OR “NSBVD” OR “accommodation” OR “convergence” AND “ADHD Treatment” OR “ADHD Diagnosis.” Seven hundred eighty articles were found in PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar search engines between 2014 and 2023. A total of 57 research articles were considered for this review after filtering out the review articles, conference proceedings, and book chapters. The articles about ADHD and its diagnosis and management were considered for this review, as shown in Fig. (3). The main objectives of this review were to find out the different treatment modalities available for ADHD, the relationship between ADHD and non-strabismic binocular vision dysfunction, and the impact of vision therapy as a treatment option for ADHD.

| ▪ Clinical Interviews ▪ Symptom Questionnaires [38-40] like Adult ADHD self-report scale V1.1(ASRS-V1.1) and Adult self-report screening scale for DMS-5(ASRS-5) ▪ Medical and Psychological Evaluation ▪ Behavioral observations ▪ Psychological Testing ▪ Diagnostic Criteria Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) ▪ Comprehensive eye examinations |

| Inattention: Six or more symptoms of inattention have persisted for at least six months to a degree that is inconsistent with the developmental level: | Hyperactivity and Impulsivity: Six or more symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity have persisted for at least six months to a degree that is inconsistent with the developmental level: |

| ▪ Pays insufficient attention to details or commits thoughtless errors at work, school, or in other activities. ▪ Has trouble maintaining focus during tasks or play activities. ▪ Does not appear to pay attention when directly addressed. ▪ Ignores directions and does not finish their homework, housework, or work-related responsibilities. ▪ Has trouble planning activities and tasks. ▪ Is unwilling to perform tasks that demand prolonged mental effort because they are unpleasant or uncomfortable. ▪ Misplaces items required for jobs or activities. ▪ Easily sidetracked by unrelated stimuli. ▪ Forgetful throughout routine tasks. |

▪ Moves their hands, feet, or seat while fidgeting. ▪ Stands up while it is expected that they stay seated. ▪ Moves around or climbs in inappropriate places (in adults or teenagers, may be restricted to irrational emotions of restlessness). ▪ Unable to play or partake in quiet activities. ▪ “On the go,” acting as if “driven by a motor.” ▪ Talks way too much. ▪ Answers are blurted out before all the questions have been answered. ▪ Has trouble waiting for their turn. ▪ Intrudes on or interrupts others. |

Paper selection flow chart. The flowchart provides information about the studies that were ultimately included in this review, as well as the search approach.

4. RESULTS

4.1. COMORBIDITIES AND ASSOCIATED CONDITIONS

Comorbidities and associated conditions can significantly impact the lives of individuals with ADHD, exacerbating the challenges they face and requiring additional support and treatment. Some of the commonly observed comorbidities and associated conditions of ADHD, such as, oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and conduct disorder (CD), learning disabilities, mood disorders, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), substance abuse disorders, sleep disorders, tic disorders, and obesity have been discussed in this study. It is important to note that not all individuals with ADHD experience comorbidities or associated conditions. The presence of these conditions varies among individuals, and the severity can also differ. It is important to note that with appropriate interventions and support, children with ADHD can thrive and lead fulfilling lives. Adults with ADHD tend to experience more internal restlessness rather than external hyperactivity. Living with ADHD as an adult can present numerous challenges. They may find it challenging to meet deadlines, prioritize tasks, and sustain attention during lengthy or monotonous activities. This can lead to increased stress, underachievement, feelings of frustration, and low self-esteem. Adults with ADHD may also face challenges in their personal relationships [29, 33]. Assessment and diagnosis of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) was a big challenge to depreciate from its comorbidity. ADHD diagnosis involves a comprehensive evaluation of an individual's symptoms, behavior, and history to determine the presence and severity of the disorder [34]. The assessment process typically includes multiple sources of information, such as interviews, questionnaires, observations, and psychological testing, along with comprehensive eye examinations to assess binocular vision function. A common onset for ADHD occurs in childhood, and it can last throughout adolescence and maturity. Before the age of 12, several symptoms were evident and can be seen in two or more contexts (such as the home, school, workplace, or social setting). It is important to note that only qualified healthcare professionals, such as psychiatrists, psychologists, optometrists, or pediatricians, should perform the assessment and diagnosis of ADHD [35-37].

It is important to note that diagnosing ADHD is a complex process, and misdiagnosis or overdiagnosis can occur. A comprehensive assessment ensures that other possible explanations for the symptoms are considered and that an accurate diagnosis is made. Overall, the assessment and diagnosis of ADHD involve a multifaceted approach [6, 35] that integrates information from various sources, as shown in Table 1.

4.2. Multimodal Management

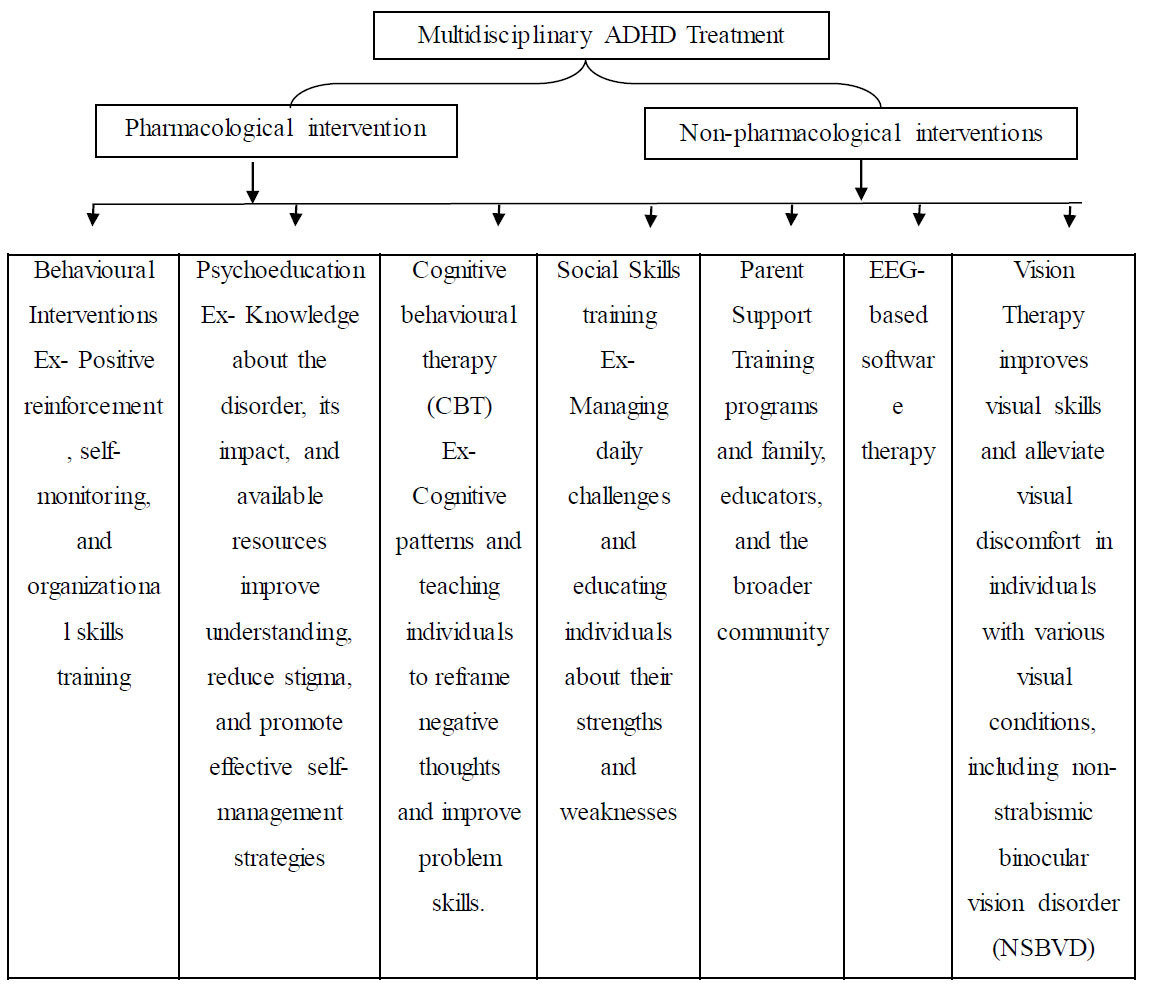

Managing ADHD typically involves a multimodal treatment approach that combines different strategies and interventions tailored to the individual's specific needs. This approach recognizes the heterogeneity of ADHD symptoms and acknowledges that a “one-size-fits-all” approach may not be effective for everyone. What works for one individual may not work for another, therefore, a personalized, complementary, and alternative medicine approach is essential [41]. It typically involves a combination of medication, behavioral interventions, psychoeducation, parent-child interaction therapy, and support [42]. Medication is often a cornerstone of ADHD treatment, especially for individuals with moderate to severe symptoms. Stimulant medications, such as methylphenidate or amphetamines, are commonly prescribed [43] and have been shown to reduce hyperactivity and impulsivity and improve attention and executive functioning in many individuals, and all the treatment options are available in Fig. (4). However, medication alone may not be sufficient for comprehensive ADHD management [44], and long uses of medication create multiple adverse effects on children, adolescents, and adults, such as decreased appetite, weight loss, dyspepsia, abdominal pain, stomach ache, irritability, mood disorders, dizziness, anorexia, nausea, somnolence, and vomiting [45-47]. Non-pharmacological interventions play a crucial role in the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Non-pharmaco- logical approaches can be used as standalone inter- ventions or in combination with medication to enhance the overall treatment outcome. These interventions focus on addressing various aspects of ADHD, such as improving attention, impulsivity control, organizational skills, and behavioral management [48]. Some commonly employed non-pharmacological treatment approaches for ADHD are given in the study [43, 49, 50], including electro- encephalographic (EEG) based, which are used for diagnostics and management purposes both [51-61].

Multidisciplinary ADHD treatment options available, including pharmacological and non-pharmacological.

5. DISCUSSION

Vision therapy for NSBVD involves a series of specialized eye exercises and visual activities tailored to the individual's specific needs, and it is also dependent on individual refractive status [62], vergence [63], stereo acuity, fusional vergence amplitudes [64], convergence insufficiency [25, 65, 66], near point of convergence (NPC) [24], accommodation problem [67], saccade [68] This condition could be improved by the help of vision therapy or orthoptic exercise. The treatment is typically conducted under the guidance of a trained optometrist or, vision therapist, or orthoptist and follows a structured program. The therapy aims to enhance the coordination and teamwork between the eyes, improve eye movement control, enhance focusing abilities, and strengthen visual processing skills, which is shown in Fig. (2) [69-73].

Furthermore, by addressing NSBVD through vision therapy techniques, which were mentioned in Table 3, ADHD patients may experience several benefits. Improved eye coordination and focusing abilities can positively impact reading skills, attention, and concentration. Enhanced visual processing and perception skills can contribute to better comprehension, visual memory, and overall academic performance [74]. Reducing visual discomfort and fatigue can alleviate the strain on the visual system, potentially leading to a reduction in ADHD-related symptoms. It is significant to stress that vision therapy should be incorporated as part of a thorough treatment strategy for those with ADHD [74]. Consulting with healthcare professionals, such as psychologists, occupational therapists, optometrists, and educators, can help determine the most suitable treatment plan and ensure a holistic approach to address the various aspects of the condition for each individual. There were a few studies that showed that signal processing and convolution neural networks can help to diagnose and management of brain-related problems [75-78]. Furthermore, the evolving understanding of ADHD through comprehensive research, clinicians and partitioners can improve diagnostic accuracy, develop targeted treatments, and enhance the overall well-being and quality of life for individuals with ADHD. While medication and behavioral therapies are commonly used in the treatment of ADHD, researchers and clinicians continue to explore alternative approaches to improve outcomes for individuals with this condition. The possible involvement of vision therapy treatment is one area of investigation, particularly in resolving non-strabismic binocular vision impairments in ADHD patients [79].

CONCLUSION

The current treatment strategy for ADHD includes a combination of medication, behavioral interventions, psychotherapy, occupational therapy, psychoeducation, parent-child interaction therapy, and support, which has shown improvement, but this treatment does not include vision-related treatment. Several studies show that non-strabismic binocular vision dysfunction (NSBVD) has been linked to ADHD symptoms, and vision therapy for NSBVD improved ADHD symptoms, although there was still more research needed. The potential advantages of vision therapy designed especially for people with ADHD and non-strabismic binocular vision impairments have only been briefly studied. There is currently a research gap in determining the efficacy of vision therapy as a treatment option for ADHD symptoms despite the intriguing association between non-strabismic binocular vision impairments and ADHD. Future studies should concentrate on carrying out sizable, randomized controlled trials that assess the effects of vision therapy on ADHD symptoms in people with non-strabismic binocular vision impairments in order to fill this knowledge gap. Moreover, by closing the research gap in the field of vision therapy for non-strabismic binocular vision abnormalities in ADHD, clinicians and practitioners can gain a deeper understanding of the potential benefits and limitations of this treatment approach. Such knowledge can guide clinicians in developing comprehensive and personalized interventions that consider the unique visual needs of individuals with ADHD, leading to improved outcomes and quality of life for those affected by this condition.

AUTHOR’S CONTRIBUTION

R.T., K.K., A.D: Study conception and design; S.S.: Data collection; S.S., R.T., K.K.: Analysis and interpretation of results; S. S.: Draft manuscript; S.S., R.T., K.K., A.D.: Review of Final Draft of Manuscript;.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| ADHD | = Attention-deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder |

| NSBVD | = Non-strabismic Binocular Vision Disorder |

| ADD | = Attention Deficit Disorder |

| EEG | = Electroencephalography |

| BCI | = Brain-Computer Interface |