All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Cortical Brain Regions Associated with Color Processing: An FMRi Study

Abstract

To clarify whether the neural pathways concerning color processing are the same for natural objects, for artifacts objects and for non-objects we examined brain responses measured with functional magnetic resonance imaging (FMRI) during a covert naming task including the factors color (color vs. black&white (B&W)) and stimulus type (natural vs. artifacts vs. non-objects). Our results indicate that the superior parietal lobule and precuneus (BA 7) bilaterally, the right hippocampus and the right fusifom gyrus (V4) make part of a network responsible for color processing both for natural objects and artifacts, but not for non-objects. When color objects (both natural and artifacts) were contrasted with color non-objects we observed activations in the right parahippocampal gyrus (BA 35/36), the superior parietal lobule (BA 7) bilaterally, the left inferior middle temporal region (BA 20/21) and the inferior and superior frontal regions (BA 10/11/47). These additional activations suggest that colored objects recruit brain regions that are related to visual semantic information/retrieval and brain regions related to visuo-spatial processing. Overall, the results suggest that color information is an attribute that can improve object recognition (behavioral results) and activate a specific neural network related to visual semantic information that is more extensive than for B&W objects during object recognition.

INTRODUCTION

Traditionally, theories about object recognition have emphasized the role of shape information in higher-level vision [1, 2]. More recently, data from behavioral studies, neuroimaging, and neuropsychological studies have suggested that surface features, such as color, also contribute to object recognition [for a review, 3]. However, the conditions under which surface color improves object recognition are not well understood. One general idea is that surface color improves the recognition of objects from natural categories, but not the recognition of artifact categories [4-6]. Humphreys and colleagues showed that objects from structurally similar categories, such as natural objects, take longer to identify than items from structurally dissimilar categories, such as artifacts, because the representations of structurally similar objects are more likely to be co-activated, therefore resulting in greater levels of competition within the object recognition system. Apparently, surface details such as color can help in resolving this competition [7-9]. Another potential reason that color information might help in recognizing natural objects is color diagnosticity. Color diagnosticity means the degree to which a particular object is associated with a specific color. Several experiments have shown that visual recognition of diagnostic colored objects benefits from surface color information, whereas recognition of non-diagnostic colored objects does not [10-12]. Typically, natural objects are more strongly associated with a specific color than artifacts. For example, a strawberry – a diagnostic colored object – is clearly associated with the color red, whereas a comb – a non-diagnostic colored object – is not strongly associated with any specific color when using color as a cue for object identification [6]. Nagai and Yokosawa [10] studied the interaction between color diagnosticity and semantic category in order to determine whether surface color helps in the recognition of diagnostic colored objects independently from their semantic category. In a classification experiment, surface color improved the recognition of diagnostic colored objects independently from their category, supporting the hypothesis that color diagnosticity is an important cue for object recognition.

In this study, we used functional magnetic resonance imaging (FMRI) to investigate whether color information plays a different role in the recognition of natural objects compared to artifacts. We examined FMRI responses during a naming task that involved natural objects and artifacts presented in both color and black & white (B&W). The color diagnosticity was kept constant between the two categories [13]. If color information plays a different role in the recognition of artifacts compared to natural objects, then different brain regions should be engaged during the naming of colored objects from different categories.

The neural correlates of color processing have been thoroughly investigated. Previous functional neuroimaging studies have associated area V4, located within the fusiform gyrus, as a centre of color perception in the human brain [14-20]. At the neuroanatomical level, area V4 is involved in color constancy operations [14, 21], color ordering tasks [22], object color recognition [23-25], conscious color perception [26], color imagery [27] and color knowledge [28]. Whereas V4 has been associated with color perception, the left inferior temporal gyrus has been described as the site of stored information about color [23, 29]. For example, Chao and Martin [23] argue that the cortical areas that subserve color knowledge are distinct from the cortical areas that subserve color perception.

With regard to colored object recognition, Zeki and Marini [25] found that both naturally and unnaturally colored objects activated a pathway extending from the posterior occipital V1 to the posterior fusiform V4. In addition to the posterior parts of the fusiform gyrus, naturally colored objects activated the medial temporal lobe and the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex. These results suggest three broad cortical stages for color processing. The first stage is based in V1, and possibly V2, and is mainly concerned with registering the presence and intensity of different wavelengths and wavelength differences. The second stage, supported by V4, involves automatic color constancy operations and is independent from memory operations, perceptual judgment or learning. The third and final stage, based in the inferior temporal and frontal cortices, processes information for naturally colored objects and involves memory, judgment and learning [25].

One question of interest in this context is the role of surface color when color is a property of an object compared to when color is part of an abstract composition or a non-object. According to the three-stage model for color processing outlined by Zeki and Marini [25], colored natural objects and artifacts should engage brain regions involved in the third stage of color processing, whereas colored non-objects should only engage brain regions involved in the first two stages. To address this issue, in addition to natural objects and artifacts, we included non-objects presented in color and in B&W.

In summary, in the present FMRI study, we investigated whether the neural correlates of color information are the same for natural objects and artifacts. We also assessed the brain regions that are specific for color when color is a property of a recognizable object compared to when color is part of an unrecognizable composition. To address these issues, we examined FMRI responses in a silent naming task with two factors: color (color vs. B&W) and stimulus type (natural objects vs. artifacts vs. non-objects). We expected to find fusiform gyrus (V4) activation in the color vs. B&W stimuli (for both objects and non-objects), confirming that the fusiform gyrus is the brain center for color perception. Additionally, we hypothesized that colored natural objects and artifacts would engage brain regions involved with color knowledge information and retrieval (inferior temporal and frontal activation) to a greater degree compared with B&W natural objects and artifacts.

METHODS

Participants

Twenty right-handed Portuguese native speakers [mean age (± std) = 22 ± 4 years; mean years of education (± std) = 14 ± 1 years; 5 men and 15 women"mean age (± std) = 22 ± 4 years; mean years of education (± std) = 14 ± 1 years; 5 men and 15 women] with normal or corrected-to-normal vision participated in the study. All subjects completed health questionnaires prior to scanning, and none reported a history of head injury or other neurological or psychiatric problems. All subjects read and signed an informed consent form describing the procedures according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the local ethics committee.

Stimulus Material

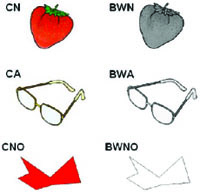

We selected 56 drawings from the Snodgrass and Vanderwart set [30]. Twenty-eight objects were from natural categories (animals and fruits) and twenty-eight were artifacts (tools and vehicles; see Table 1). We also constructed 28 matching non-objects (constructed with the Paint-software and approximately matched for visual complexity). The non-objects were scrambled lines and shapes without any obvious conventional meaning. All images were presented both in color and B&W. The color version was selected from the set of Rossion and Pourtois [13] and the B&W version was selected from the grey-scale set of Rossion and Pourtois [13]. We opted for the grey-scale version and not the original B&W version from the Snodgrass and Vanderwart [30] set in order to keep the luminance and brightness constant over the color and B&W conditions (Fig. 1). All 56 images were classified according to familiarity based on norms for the Portuguese population [31], color diagnosticity based on Rossion and Pourtois [13], and visual complexity based on the original work of Snodgrass and Vanderwart [30]. There was no significant difference between stimulus types on these variables (P > 0.10). In addition, the natural and artifact stimuli were matched in terms of syllabic length (P > 0.20). Stimuli luminance, measured using Adobe Photoshop 7.0, of the natural objects, artifacts and non-objects (color and B&W versions) was similar (overall, Kruskall-Wallis ANOVA H < 1.6, P > 0.50).

Stimuli Used in Experiment

| Natural Objects | Artifacts Objects |

|---|---|

| Alligator | Accordion |

| Ant | Airplane |

| Apple | Anchor |

| Bear | Barrel |

| Butterfly | Basket |

| Chicken | Bell |

| Cow | Belt |

| Dog | Boot |

| Duck | Bus |

| Fox | Car |

| Gorilla | Cigarette |

| Grapes | Drum |

| Horse | Flute |

| Lemon | Fork |

| Monkey | Glasses |

| Mushroom | Gun |

| Onion | Hammer |

| Pear | Harp |

| Pepper | Key |

| Pig | Nail |

| Potato | Needle |

| Rabbit | Nut |

| Rooster | Pencil |

| Seal | Piano |

| Squirrel | Scissors |

| Strawberry | Shoe |

| Tiger | Spoon |

| Turtle | Thimble |

Example of the stimuli used in the experiment. CN – color natural objects; BWN – B&W natural objects; CA – color artifacts objects; BWA – B&W artifacts objects; CNO – colored non-objects; BWNO – B&W non-objects.

Experimental Procedures

The stimuli were presented in a blocked design. The twenty-eight stimuli from each condition were distributed over four blocks (6 conditions x 4 blocks; seven objects in each block) resulting in twenty-four blocks. Four of each condition were allocated to two different sets (each set was composed of 84 stimuli grouped into two blocks for each condition – 2 blocks x 6 conditions x 7 stimuli). Two additional sets were constructed by changing the presentation order of the blocks in the two original sets. In each experimental set, we also included four blocks of seven baseline events, consisting of a visual fixation cross. For each subject, four sets were presented in four consecutive FMRI sessions. Altogether, 112 objects were presented to each subject per FMRI session, which included the seven experimental conditions: CN – colored natural objects; BWN – B&W natural objects; CA – colored artifacts; BWA – B&W artifacts; CNO – colored non-objects; BWNO – B&W non-objects; and finally, VF – visual fixation, which served as a baseline condition. Each subject saw each object twice per condition during the experiment, but never in the same FMRI session. Each block lasted 19.6 seconds, and each stimulus was presented for 2.8 seconds(Fig. 2).

Schematic representation of the experimental design for one FMRI session. CN – color natural objects, BWN – B&W natural objects, CA – color artifacts objects, BWA – B&W artifacts objects, CNO – colored non-objects, BWNO – B&W non-objects, VF – visual fixation. Each block lasted 19.6 seconds and each stimulus was presented for 2.8 seconds.

In four separate scanning sessions, with session order counterbalanced across subjects, subjects were asked to attentively view the picture and silently name each object, in a covert naming task. Each of the four FMRI sessions lasted 6 minutes. Subjects were also asked to silently repeat “tan-tan” for the non-objects and for the visual fixation cross in order to encourage attention to the stimuli without attaching a particular verbal label. Subjects viewed the stimuli via a mirror mounted on a head-coil (the visual angle for the stimulus presentation was approximately 8 degrees). Prior to the FMRI experiment, subjects performed an object naming task in order to familiarize themselves with the objects and for the acquisition of behavioral naming data. The verbal responses and naming times were registered for subsequent behavioral analysis. Voice detection equipment was used to register response times between the onset of the stimulus display and that of the response. The same presentation paradigm was used for the object naming task as for the FMRI experiment. The Presentation 0.7 Software (nbs.neuro-bs.com/presentation) was used to display the stimuli on a computer screen (HP Laptop with 15” screen) and to register the response times.

MRI Data Acquisition

We acquired whole head T2*-weighted EPI-BOLD MRI data with a Philips 1.5 T Intera scanner using a sequential slice acquisition sequence (TR = 2.46 s, TE = 40 ms, 90º flip-angle, 29 axial slices, slice-matrix size = 64 x 64, slice thickness = 3 mm with a slice gap = 0.4, field of view = 220 mm, isotropic voxel size = 3.4 x 3.4 x 3.4 mm3). Following the experimental session, high-resolution structural images were acquired using a T1-weighted 3D TFE (TE = 3.93 ms, 10º flip-angle, slice-matrix size = 256 x 256, field of view = 256 mm, 200 axial slices, slice thickness = 1.0 mm, isotropic voxel-size = 1 x 1 x 1 mm3).

MRI Data Analysis

Image pre-processing and statistical analysis was performed using SPM5 (www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm) implemented in MatLab (Mathworks, Sherborn, MA). The functional EPI-BOLD images were realigned and slice-time corrected, and the subject-mean functional MR images were co-registered with the corresponding structural MR images. These were subsequently anatomically normalized. The normalization transformations were generated from the structural MR images and applied to the functional MR images. The functional EPI-BOLD images were transformed into an approximate Talairach space [32] as defined by the SPM5 template and spatially filtered with an isotropic 3D spatial Gaussian kernel (FWHM = 10 mm). The FMRI data were statistically analyzed using the general linear model and statistical parametric mapping [33]. At the first level, single-subject fixed effect analyses were conducted. The linear model included one box-car regressor for each of the CN, BWN, CA, BWA, CNO, BWNO and VF conditions. We temporally convolved these explanatory variables with the canonical hemodynamic response function provided by SPM5. In addition, we also included realignment parameters to account for movement-related variability. The data were high-pass filtered (128 s) to account for various low-frequency effects. For the second-level random effect analysis, we generated single-subject contrast images for the CN, BWN, CA, BWA, CNO and BWNO conditions relative to VF.

We analyzed the contrast images in a two-way repeated measures ANOVA with the following factors: color type (color vs. B&W) and stimulus type (natural objects vs. artifacts vs. non-objects). We analyzed the natural objects and artifacts together because there was no significant difference between these conditions, whether in color or B&W. Also, there was no significant difference in CN vs. BWN or CA vs. BWA (overall, P > 0.3). Thus, we generated single-subject contrasts for the colored objects – CO (= CN + CA) and the B&W objects – BWO (= BWN + BWA). We analyzed these collapsed contrasts in a two-way repeated measures ANOVA with the following factors: color type (color vs. B&W) and stimulus type (objects vs. non-objects). Statistical inference was based on the cluster-size statistic from the relevant SPM[T] volumes. In a whole brain search, the results from the random effects analyses were initially threshold at with P < 0.005 (uncorrected) and only significant clusters at P < 0.05 (family-wise error (FWE) corrected for multiple non-independent comparisons) are reported [34]. All local maxima within significant clusters were subsequently reported with P-values corrected for multiple non-independent comparisons based on the false discovery rate [FDR, 35]. SPM[T] volumes were generated to investigate the effects of color and stimulus type. Finally, we applied a small volume correction (SVC, 5 mm radius) to regions typically involved in color perception: the fusiform gyrus (V4) ([± 28, -62, -20]) and the hippocampus ([± 36, -10, -20]) bilaterally [23, 25] and in a region in the left temporal gyrus previously described as the site of stored information about colored objects ([-56, -40, -14]) [23, 29]. All reported data are from the second-level random effect analyses. For portability of the results, we used the Talairach nomenclature [32] with the original SPM coordinates in the tables.

RESULTS

Behavioral Results

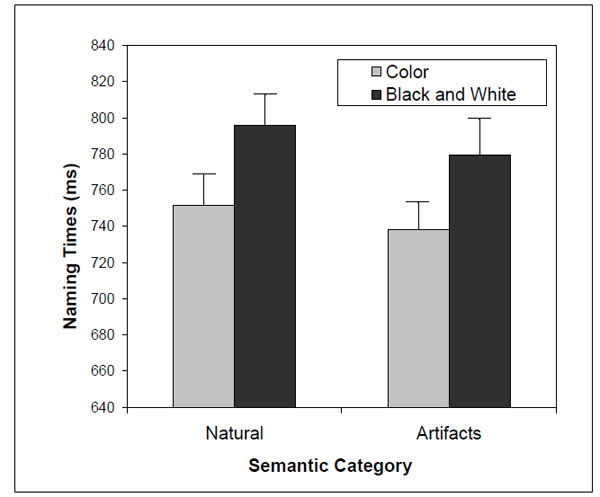

Subjects were able to correctly name all stimuli. Overall, the number of naming errors was small (<2%), so we analyzed the naming times for the correct responses with latencies within 2.5 standard deviations from the mean for each subject and condition. Excessively long or short naming latencies were excluded from further analysis because these are likely due to lapses of attention/concentration and anticipatory responses, respectively. No-response trials and misregistered responses (software failure and responses anticipated by subject vocalizations other than the naming responses) were also excluded. In total, approximately 11% of the trials were excluded (3.8% due to lapses of attention or concentration, 1.6% due to anticipatory responses, 1.5% due to incorrect responses, 0.1% due to non-answers, 3.8% due to misregistered responses). The naming times were analyzed with a repeated-measures ANOVA considering the following within factors: presentation version (color vs. B&W) and semantic category (natural objects vs. artifacts). The results showed a significant presentation version effect [F(1,19) = 30.6; η2 = 0.62; P < 0.001] – subjects were faster at naming color compared to B&W objects. The semantic category effect [F(1,19) = 2.8; η2 = 0.13; P = 0.13] and the interaction between presentation version and category [F(1,19) = 0.10; η2 = 0.005; P = 0.76] were not significant (Fig. 3).

Two-way interaction [F(1,19) = 2.8; η2= 0.13; P = 0.13] between presentation version and semantic category on naming times.

FMRI Results

Color and B&W Effects

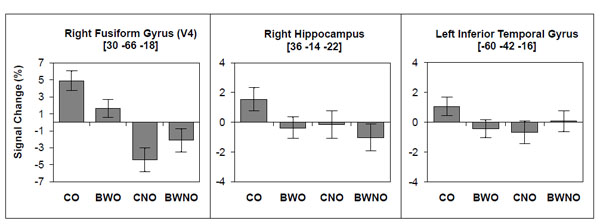

The contrast between color vs. B&W stimuli (for both objects and non-objects) did not result in any significant activation, nor did the contrast between color non-objects vs. B&W non-objects. However, the contrast between colored objects vs. B&W objects (Table 2) showed a significant cluster (P = 0.006, FWE corrected) that encompassed the superior parietal region and precuneus (BA 7) bilaterally. To further investigate the regional effects related to color processing, we used a regions-of-interest (ROI) approach in combination with small volume correction (SVC) for the family-wise error rate. We selected regions of interest based on previous investigations that studied color effect in object recognition [23, 25, 29]. These regions included the right/left fusiform gyrus (V4), the right/left hippocampus and the left inferior temporal gyrus. We investigated these regions in the following contrasts: 1) color vs. B&W stimuli; 2) color vs. B&W objects; and 3) color vs. B&W non-objects. We found significant activations (Table 3 and Fig. 4) for color vs. B&W (P = 0.032, SVC corrected) in the right hippocampus and for color vs. B&W objects in the right fusiform gyrus (V4; P = 0.011, SVC corrected), right hippocampus (P = 0.033, SVC corrected) and left temporal inferior gyrus (P = 0.037, SVC corrected). The contrast between color vs. B&W non-objects yielded no additional effects.

Color Objects and B&W Objects

| Region | Cluster Level | Coordinates | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFWE | x | y | z | |

| Color Objects versus B&W Objects | ||||

| Right superior parietal (BA 7) | 0.006 | 16 | -60 | 64 |

| Left superior parietal (BA 7) | -26 | -64 | 46 | |

| Right precuneus (BA 7) | 10 | -48 | 66 | |

| Left precuneus (BA 7) | -8 | -58 | 62 | |

SPM [T], Clusters significant at P < 0.05 corrected for multiple non-independent comparisons are reported (PFWE). Local maxima within the clusters are reported. Coordinated are the original SPM x, y, z in millimeters of the MNI space.

Small Volume Corrections in SPM [T]

| Region | Voxel Lexel | Coordinates | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z | PFWE | x | y | z | |

| Color versus B&W | |||||

| Right Hippocampus | 2.68 | 0.032 | 36 | -10 | -24 |

| Color Objects versus B&W Objects | |||||

| Right Fusiform (V4) | 3.08 | 0.011 | 30 | -66 | -18 |

| Right Hippocampus | 2.67 | 0.033 | 36 | -14 | -22 |

| Left Inferior Temporal Gyrus | 2.62 | 0.037 | -60 | -42 | -16 |

SPM [T], threshold at P < 0.005, non-corrected. PFWE SVC corrected. Coordinates are the original SPM x, y, z in millimeters of the MNI space.

BOLD signal change associated with color and B&W objects (CO, BWO) and with color and B&W non-objects (CNO, BWNO).

Color and B&W Object Recognition

The contrast between object vs. non-object stimuli resulted in two clusters of significant brain activation (P < 0.001, FWE corrected). These included the posterior occipital regions (BA 18/19), the fusiform gyrus (BA 19/37), and the inferior temporal lobe (BA 20) bilaterally (Table 4 and Fig. 5). The contrast between colored objects vs. color non-objects (Table 4 and Fig. 5) resulted in additional activations in the right parahippocampal gyrus (BA 35/36), the inferior-superior parietal lobule (BA 7/39/40) bilaterally, and in the left inferior-middle temporal region (BA 20/21). In addition, frontal regions (P = 0.006, FWE corrected) were also significantly activated in colored objects vs. colored non-objects, including the left anterior-inferior frontal region (BA 10/47) and the left superior frontal region (BA 10). The contrast between B&W objects vs. B&W non-objects activated similar brain regions as observed in objects vs. non-objects, however the activation pattern was more restricted and primarily observed in posterior brain regions (right: P = 0.021, FWE corrected; left: P = 0.009, FWE corrected; Table 4 and Fig. 5).

Objects Versus Non-Objects

| Region | Cluster Level | Coordinates | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFWE | x | y | z | |

| Objects versus Non-Objects | ||||

| Right middle occipital (BA 18/19) | <0.001 | 34 | -94 | -6 |

| Right fusiform (BA 19/37) | 36 | -66 | -18 | |

| Right inferior temporal (BA 20) | 48 | -54 | -22 | |

| Left middle occipital (BA 18/19) | < 0.001 | -46 | -90 | -8 |

| Left fusiform (BA 19/37) | -36 | -66 | -14 | |

| Left inferior temporal (BA 20) | -50 | -36 | -20 | |

| Objects Color versus Non-Objects Color | ||||

| Right middle occipital (BA 18/19) | < 0.001 | 46 | -78 | -12 |

| Right fusiform (BA 19/37) | 38 | -62 | -20 | |

| Right parahippocampal (BA 35/36) | 26 | -26 | -26 | |

| Right inferior temporal (BA 20) | 48 | -56 | -18 | |

| Left middle occipital (BA 18/19) | < 0.001 | -38 | -86 | -4 |

| Left fusiform (BA 19/37) | -42 | -60 | -16 | |

| Left inferior temporal (BA 20) | -48 | -60 | -16 | |

| Left inferior-middle temporal (BA 20/21) | -44 | -44 | -18 | |

| Right inferior-superior parietal (BA 7/39/40) | 26 | -88 | 38 | |

| Right superior parietal (BA 7) | 16 | -90 | 42 | |

| Left inferior-superior parietal (BA 7/39/40) | -22 | -80 | 42 | |

| Left superior parietal (BA 7) | -28 | -62 | 50 | |

| Left inferior frontal (BA 11/47) | 0.006 | -18 | 42 | -6 |

| Left superior frontal (BA 10) | -20 | 48 | 8 | |

| Objects B&W versus Non-Objects B&W | ||||

| Left middle occipital (BA 18/19) | 0.009 | -32 | -100 | -2 |

| Left fusiform (BA 19/20/20) | -36 | -70 | -14 | |

| Right middle occipital (BA 18/19) | 0.021 | 36 | -96 | -8 |

| Right fusiform (BA 19/20/37) | 36 | -68 | -18 | |

SPM [T], Clusters significant at P < 0.05 corrected for multiple non-independent comparisons (PFWE) are reported. Local maxima within the clusters are reported. Coordinated are the original SPM x, y, z in millimeters of the MNI space.

A - Brain regions associated with objects compared to non-objects, B - Brain regions associated with color objects compared to color non-objects, C - Brain regions associated with B&W objects compared to B&W non-objects.

DISCUSSION

In this FMRI study, we aimed to clarify whether the neural substrates related to color information are the same when color is a property of a recognizable object, namely natural objects and artifacts, compared to when color is a property of an unrecognizable object, such as abstract compositions.

Color Effects on Objects and Non-Objects

According to the three cortical stages model for color processing proposed by Zeki and Marini [25], we expected that color information presented in recognizable objects would activate the V4 area as well as brain areas involved in memory, classification, and learning operations. Our results show that color compared to B&W objects activated the right V4 area. In addition, we also observed brain activations in regions that are typically associated with color perception, the right hippocampus and superior parietal/precuneus region, corroborating previous findings [14, 18, 20, 23, 25, 27].

To better understand the role of color information in the recognition of familiar objects, we explored brain activation during the processing of colored objects and colored non-objects. In general, object naming activated brain regions that extended from the occipital to the inferior temporal regions, including fusiform activation, consistent with earlier neuroimaging studies on object recognition [36-42]. Additionally, colored objects compared to colored non-objects activated an extensive network of brain regions including the left inferior temporal gyrus, right parahippocampal gyrus, left inferior and superior parietal lobule, and left superior and anterior-inferior frontal regions. These activations were exclusive for colored objects and were not found when B&W objects were contrasted against B&W non-objects, suggesting that color plays an important role in accessing the semantic level during object naming processes, as initially suggested by Zeki and Marini [25]. We did not find any particular brain region that responded only to B&W object naming, suggesting that the recognition of B&W objects does not add a cognitive operation to the recognition of colored objects.

The temporal and frontal activations found during colored object naming suggest that color engages access to the semantic network that contains information/knowledge about the objects. Parahippocampal gyrus activation has been reported in post-recognition processes, such as visual and semantic analysis [43-45], and during the encoding and retrieval of color information [46, 47]. It has been suggested that the inferior temporal gyrus stores information about colored objects [29, 48]. The frontal activations observed during colored object naming suggest that the recognition of a colored object engages a semantic network that is more active in comparison to B&W object recognition. Left inferior frontal activations have been reported during semantic knowledge tasks [40, 49-53]. On the other hand, the activations observed in the left inferior and superior parietal lobule might suggest that color is a feature that helps in the encoding of visuo-spatial properties of objects [54, 55]. An alternative explanation is that the activated parietal and frontal regions during the recognition of colored objects versus colored non-objects results from an increase in attention due to color information [56]. However, if this was the case, then we should have also seen this pattern of activation when colored non-objects were contrasted with B&W non-objects.

Regarding the role of color information in the processing of non-objects, we expected that color information would engage V4. However, the contrast between colored versus B&W non-objects did not yield an additional significant activation. The absence of V4 activation in the colored non-object condition might be related to methodological issues such as a lack of sensitivity or to experimental design issues. Previous studies that reported V4 activation in response to abstract colored stimuli used transient on/off presentations of each stimulus at a rate of 1 Hz [18, 25].

We should point out that there are other variables that could contribute to the pattern of the observed results. In every trial, subjects had to covertly utter the name of the recognized object or utter “tan-tan” for non-objects. In the case of non-objects, subjects knew from the start of the block that they would only have to utter “tan-tan” while the block was running, without any further processing. In contrast, for object blocks, subjects had to recognize and name every object. Consequently, producing the non-sense word “tan-tan” for all non-objects did not require the same level of complexity as retrieving lexical information for certain objects. This may therefore lead to condition-dependent biases in the associated attention state, lexical retrieval and covert naming. However, when we suggest that the colored objects (vs. colored non-objects) activated a more extensive brain network than the B&W objects (vs. B&W non- brain network than the B&W objects (vs. B&W non-objects), we are excluding the interference associated with attention state, lexical retrieval and covert naming because these effects are present in the contrast between both colored and B&W objects vs. non-objects.

Color Effects in Natural Objects and Artifacts

Our results show that the brain regions responsible for color processing are the same when color is a property of natural objects and artifacts, suggesting that color information has the same role in the recognition of natural objects and artifacts. This result does not support the proposal of Humphreys and colleagues [4, 6] and suggests that previous behavioral differences reported in the processing of natural objects and artifacts might be due to color diagnosticity rather than to semantic category. When color diagnosticity is controlled, as in our study, no differences in the recognition of colored natural objects and artifacts were found in the FMRI or the behavioral results. Moreover, our results showed that the brain regions responsible for processing natural objects and artifacts are the same, both when the objects are presented in color and in B&W. Several candidate regions have emerged as potential sites that may be strongly involved in natural object recognition, including the medial occipital, right occipito-temporal and left anterior temporal cortex [48, 57-59]. On the other hand, the fusiform gyrus, left precentral gyrus and left posterior middle temporal cortex have been reported as the sites that may be strongly involved in the recognition of artifacts compared with objects from other categories [48, 58]. Although category-specific brain activation patterns have been investigated in several neuroimaging studies, the results have not been consistent across studies. For example, Joseph [60] performed a meta-analysis of stereotactic coordinates to determine if category membership predicts patterns of brain region activation across different studies. The author found no more than 50% convergence for the recognition of both natural objects and artifacts in any brain region.

CONCLUSIONS

Colored objects activate the inferior temporal, parahippocampal and inferior frontal brain regions, areas that are typically involved in visual semantic processing and retrieval. This suggests that the recognition of a colored object activates a semantic network in addition to the one that is active during the recognition of B&W objects. The engagement of the semantic network when color is present in the objects led subjects to name colored objects more quickly than B&W objects. These results suggest that color information can have an important role during the visual recognition process for familiar and recognizable objects (both natural objects and artifacts), facilitating semantic retrieval. On the other hand, color information present in non-objects does not activate any brain region involved in the recognition process itself, but only engages the posterior cingulate/precuneus. Although the role of color information in the recognition of non-objects is not as clear as the role that color plays in object recognition, we suggest that color information for non-objects induces processes related to visual imagery and mental image representations, perhaps encouraging operations that attempt to associate a non-object with already stored knowledge of familiar objects. Additionally, we did not find any particular brain region that responded only to the naming of B&W objects, suggesting that the recognition of a B&W object does not add a cognitive operation to the recognition of a colored object.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT/POCTI/46955/PSI/2002; IBB/CBME, LA, FEDER/POCI 2010), and a PhD fellowship to Inês Bramão (FCT/SFRH/BD/27381/2006). We also want to thank Paulo Tinoco and Lambertine Tackenberg at Clínica Fernando Sancho, Faro, Portugal, for their help with the FMRI data acquisition.