All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Sphenoclival Intraosseous Lipoma in Skull Base

Abstract

Intraosseous lipoma is a rare benign tumor, mostly occurring in lower limb especially in os calcis and the metaphyses of long bones. Intraosseous lipoma of the skull is even rarer, with 12 cases having been reported to involve the sphenoid bone in the literature. We present the third reported case of sphenoclival intraosseous lipoma in a 43-year-old man with headache, hyperprolactinemia and visual disturbance. Performed Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) revealed pituitary macroadenoma as well as a mildly expansile lesion with high signal intensity on both T1- and T2-weighted sequences within the left greater wing of the sphenoid and the clivus. The patient refused to undergo surgical removal of pituitary macroadenoma and medical treatment was initiated instead; thereafter, follow up Computed Tomography (CT) and MRI scans revealed regression of the pituitary macroadenoma whereas the sphenoclival lesion was depicted as a welldefined fat-containing intraosseous lesion which showed no perceptible growth, 17 months later.

INTRODUCTION

Identification of fat-containing lesions as well as dystrophic calcification and cyst formation is now facilitated with the advent of Computed Tomography (CT) and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) [1, 2]. Lipoma is a slowly growing tumor with characteristic CT and MR features [3]. Thus, accurate identification of intraosseous lipoma is essential to avoid surgery; unless, the critical location of the lesion and impression on adjacent nerves preclude conservative therapies. Intraosseous lipoma is a rare variant of lipoma, first reported in 1880 [4]. Involvement of the skull is even rarer [5-7]. To best of our knowledge, 12 cases of sphenoidal bone involvement have been reported in the literature [8]; among them 2 cases have been shown to involve sphenoclival area [9, 10]; hence, we are reporting the third case of sphenoclival intraosseus lipoma.

CASE REPORT

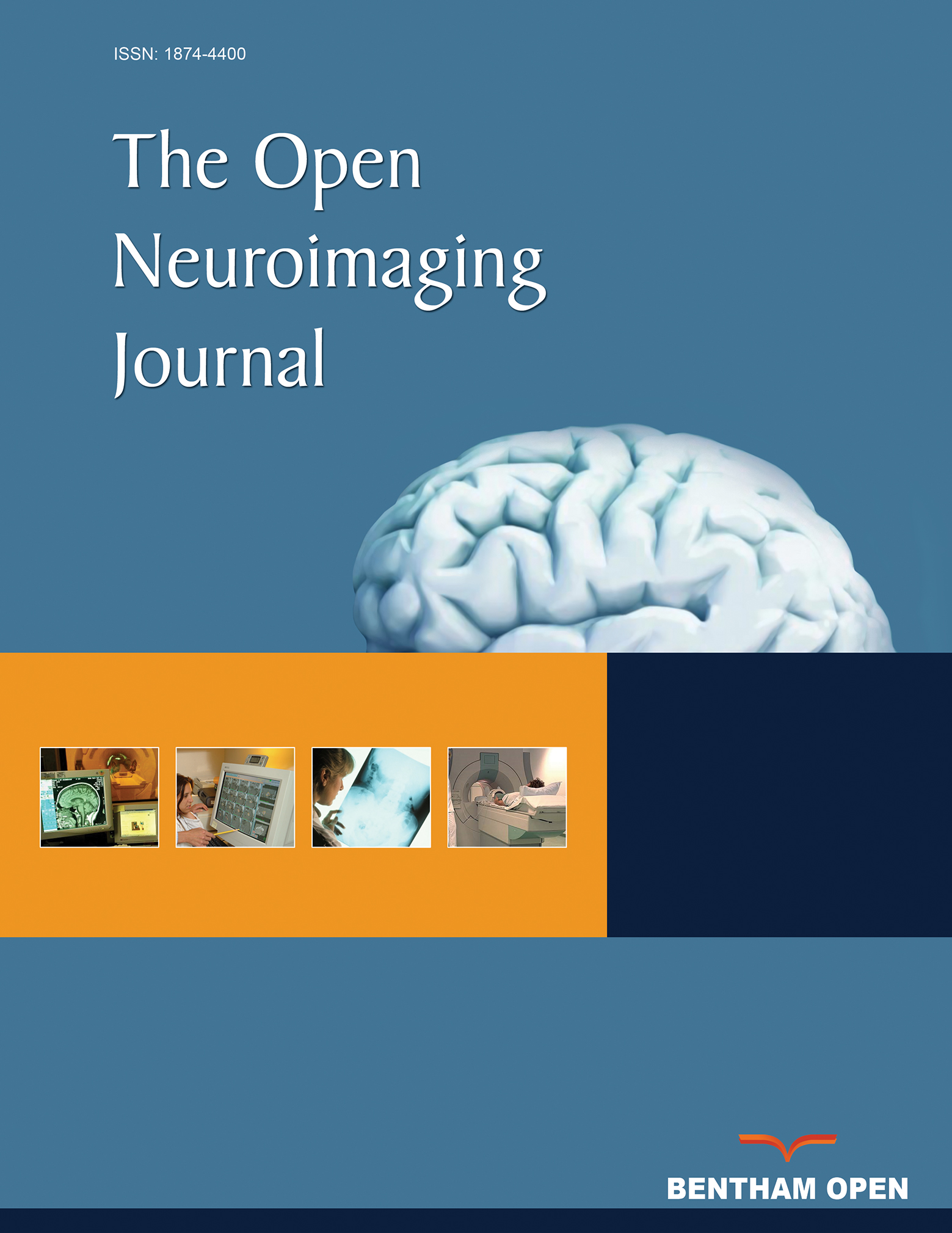

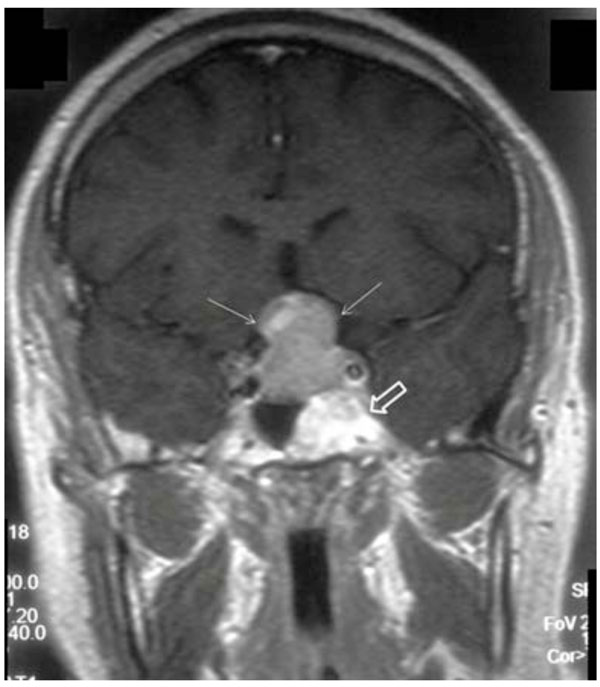

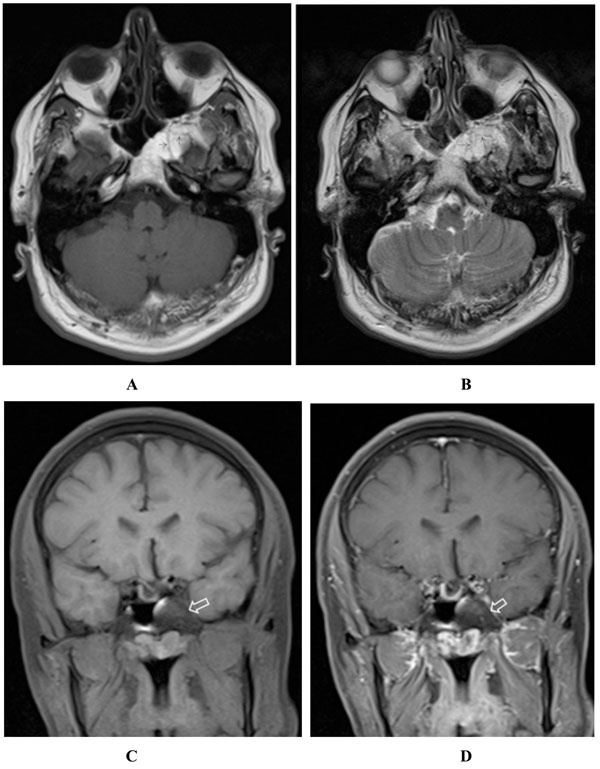

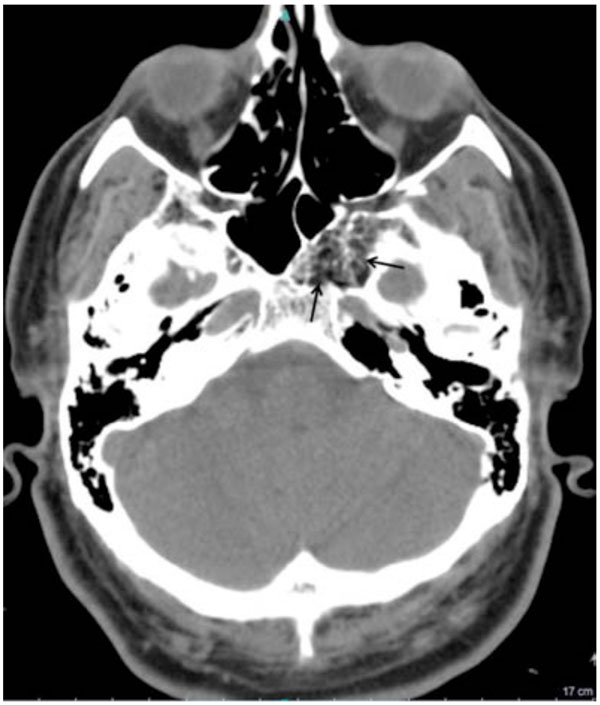

A 43-year-old female was referred to our hospital with headache, hyperprolactinemia (500ng/ml) and left visual disturbance in June 2010. Performed Visual Evoked Potential (VEP) test revealed P100 wave latency and also a significant decrease in its amplitude in the left orbit, indicating visual pathway dysfunction. The first MRI scan (Fig. 1) demonstrated pituitary macroadenoma, accompanied by a hyper intense lesion on both T1- and T2-weighted sequences within the greater wing of the left sphenoid and the clivus. The sphenoclival lesion had mildly expanded the involved bones. No obvious tumoral invasion into sellar or parasellar areas was detected; nevertheless, mild impression on left parasellar fossa could not be excluded with certainty. The lesion was fairly well-circumscribed with increased signal intensity on both T1- and T2-weighted images, most consistent with intraosseous lipoma. No abnormal enhancement was detected after intravenous contrast agent administration. The patient was recommended to undergo surgical treatment of pituitary macroadenoma; however, the patient refused for personal reasons. Thus, medical treatment was initiated. Follow-up pituitary MR scan, at 6 months interval (Fig. 2) showed no tumoral growth in intraosseous lesion while the pituitary macroadenoma had remarkably decreased in size. Further follow-up MR scans, performed 12 and 17 months (Fig. 3 A-D) later, also revealed no significant growth in the sphenoclival intraossous lesion. After applying fat suppression pulse, striking decrease in signal intensity of the lesion was depicted. The patient also underwent brain CT (Fig. 4) and Hounsfield Unit measurements of the sphenoclival lesion, in CT exam were between −50 and −100, confirming the fatty nature of the tumor. The patient’s visual disturbance also remained unchanged since the first study, suggesting that like other parts of the body, intraossous lipoma is a benign tumor with an indolent clinical course. However, as in our patient, when it occurs near to important intracranial nerves, even a mild expansion of the bone may cause impression on the adjacent nerves, leading to corresponding neurologic deficits.

Post-contrast coronal T1-weighted image demonstrates pituitary macroadenoma (white narrow arrows) with extension into suprasellar area. Incidental note is made of a hypersignal lesion in the left sphenoclival area (open arrow).

Post-contrast sagittal T1weighted image, after 6 months, reveals marked decrease in size of the pituitary mass (white narrow arrow). The clival lesion is also detected with lobulated; albeit, well-defined border (open arrow).

(A-D) Axial T1- (A), axial T2- (B) and fat-suppressed coronal T1- (C) weighted images, after 17 months, demonstrate high T1 and T2 signal lesion within the clivus and left sphenoid wing which exhibits complete signal loss after applying fat suppression pulse (open arrow in C). Some internal hyposignal septa (arrows in A & B) are also appreciated, possibly due to the residual trabeculation after bone resorption. The lesion shows no enhancement in post contrast fat-suppressed T1-weighted image (open arrow in D).

Performed axial CT scan depicts the fat attenuation of the sphenoclival mass (arrows) with associated internal ossified trabecular septa. The expansion of left greater wing is shown to better advantage. The mean density of the lesion was between -50 and -100 Hounsfield Unit.

DISCUSSION

Intraosseous lipoma is a rare benign tumor, accounting for approximately 0.1% of bone tumors. It usually occurs in calcaneus, intertrochanteric and subtrochanteric regions of the femur, pelvis and flat bones. Typical benign radiographic manifestations of intraosseous lipoma may preclude further evaluation with MRI or CT. Thus, its prevalence might be underestimated. Milgram [11] analyzed 61 patients with intraosseous lipoma and divided the tumor into three stages. In stage I, solid lesions demonstrate viable fat. Stages II transitional lesions contain regions of viable fat and fat necrosis, as well as areas of dystrophic calcification. Finally, in stages III advanced intraosseous lipomas show involutional changes with extensive fat necrosis, cyst formation, calcification, and reactive new bone formation. Likewise, intraosseous lipoma has variable radiographic, CT and MRI appearances, according to its involutional stage.

In stage I, the lesion is radiolucent in plain radiographic study. It is usually surrounded by a rim of sclerosis. CT reveals trabecular bone resorption with associated bone expansion while MRI images demonstrate signal intensity identical to that of subcutaneous fat. The peripheral sclerosis exhibits a rim of hyposignal intensity on both T1- and T2-weighted sequences.

In stage II, radiography shows a mixed radiolucent and sclerotic mass, likely representing viable fat and areas of calcification or fat necrosis, respectively. On CT exam, Stage II lesions exhibit regions of fat attenuation corresponding to viable fat and areas of increased density related to fat necrosis or calcification. As expected, MRI features of intraosseous lipoma are also parallel to those of pathologic stages and it exhibits areas of fat intensity and central area of low T1- and T2-wieghted signal changes; the latter represent central calcification. Peripheral sclerotic rim may also present.

Stage III lesions are denser than former ones in radiographic studies, resulting from extensive necrosis of fat components and calcification. On CT, areas of fat, soft-tissue and calcium attenuation are appreciated. Peripheral rim of fat attenuation, as well as peripheral calcification may differentiate intraosseous lipoma from bone infarct. In stage III lesions, one can again identify peripheral rim of fat intensity, areas of central calcification, fat necrosis and a thick rim of sclerosis. Thick rim of fat is hypersignal on both T1- and T2-weighted sequences and central area of fat necrosis have variable and high signal on T1- and T2-weighted images, respectively [2].

Nevertheless, imaging findings in our patient is not completely attributable to any of the above-mentioned patterns. In fact, the honey comb appearance of the lesion in the imaging of this patient differs from those seen in most cases of intraosseous lipoma in long bones and it rather resembles a fatty marrow island within an enlarged normal cancellous bone.

CONCLUSION

Familiarity with the typical appearance of intraosseous lipoma in both MRI and CT is essential for radiologist to diagnose this benign lesion and fat saturation pulse in MRI and measuring the attenuation of the lesion in CT are the two useful techniques which help us improve our diagnostic accuracy in addition to histopathologic confirmation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Declared none.